Chapter 1. Board Meeting

"What is the actual financial position as of today?" I asked.

“Well, we owe our suppliers £339K, VAT of £79K, £29K of PAYE and we also owe the Factoring company £120K”, said Monika Bassett, my Mum.

“So, we actually owe almost £600K?

Wow.” I said glumly.

“How much is in the bank?”

“Actually, we have literally no money.”

“Can it be any worse?” I asked.

“Since the financial restructure of last year, we have not been able to keep up with the lease repayments either and are now £15,000 in arrears, so we are now in danger of having our cameras repossessed.”

“It gets worse!”

…and the insurance company DEFINITELY said that they wouldn’t honour the insurance claim from the burglary? We were relying on that £600K.”

“No. They told me definitively today that this was their final decision.”

“BASTARDS! They could have told us this six months ago so that we could have cut our costs further instead of waiting for a pay-out that they had no intention of honouring.

And now it is just too late…,” I said.

“We owe almost £600K which works out at about five months of revenue; we have very little equipment that wasn’t stolen which we can rent out and actually earn us revenue; we owe £15K in overdue leases and you are telling me that we have NO MONEY?”

“…and don’t forget the £250K of personal guarantees that we have to the leasing companies if we go bust,” said Jeff Bassett, my Dad.

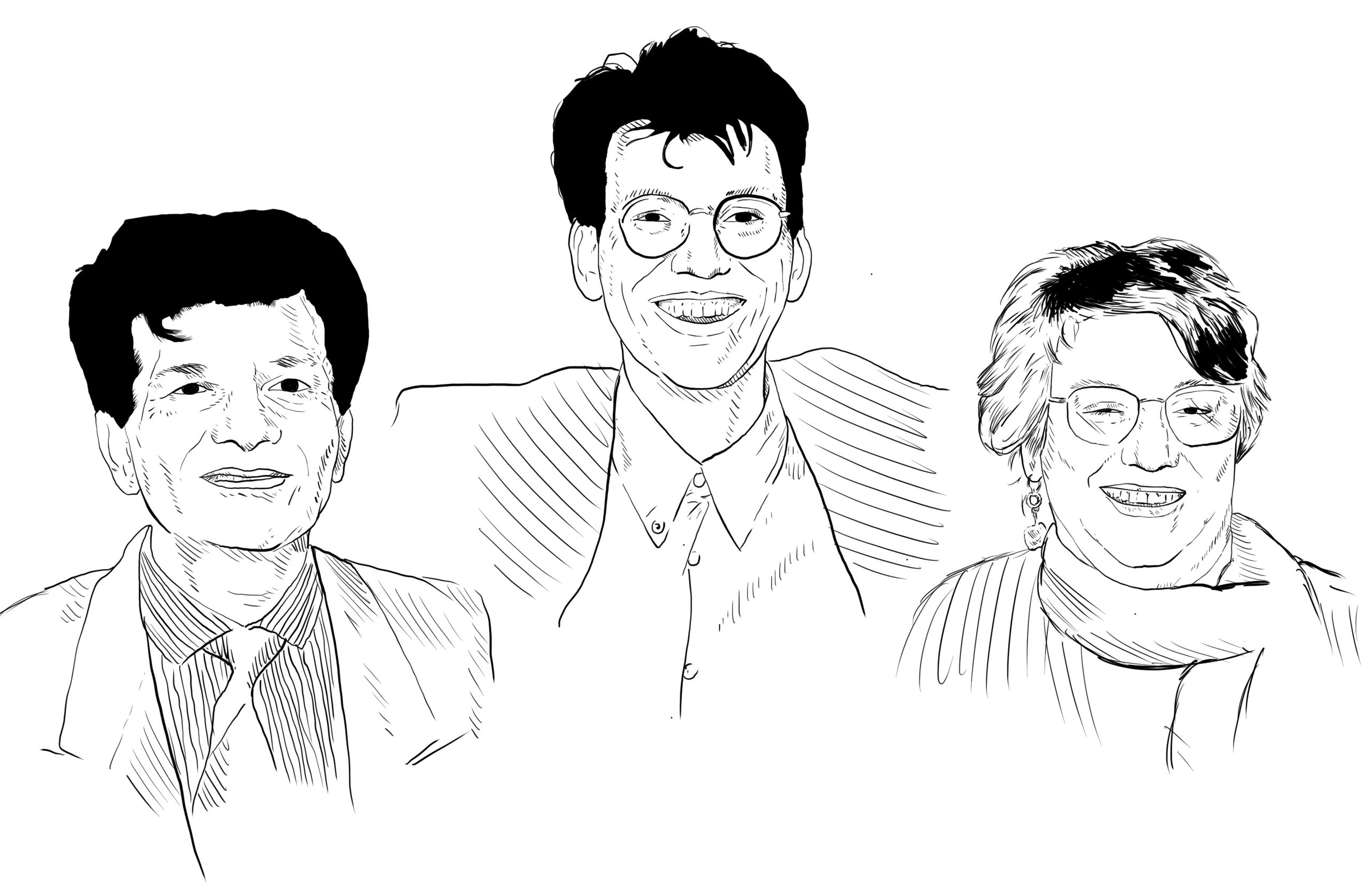

The three members of the board of VMI all looked at each other grimly. Business failure looked certain.

“Right then, I am going to have to think of a plan.” I said.

This was met by silence.

“I’m off for a bike ride. Geneva to Cannes through the Alps should do it. 1000km and 21 Alps. See you in two weeks and I WILL have a plan.”

Chapter 2. Early Years

My Dad taught me that if you see everyone running in one direction, then look at where they are coming from and consider running in that direction, as they may have all missed something.

The essence of this idea has come to define the person that I have become and for me, this started forming at a very early age.

Raised in North West London in 1968 from an immigrant family, it was never easy for me to fit in.

My Mum was the youngest of four sisters and born in Nuremberg in Northern Germany just after the war. Moving to London in her teens to work as an au pair, she had enrolled in a local college to improve her English and it was there that she met my Dad. Although she always meant well, her extremely matter of fact and blunt manner proclaimed that the world should take her as she was and this could come across as a bit abrasive.

Dad was the polar opposite. Born in Hyderabad in India, of Persian and Turkish parents, he was just five years old in 1947 when Pakistan was partitioned from India. Being Muslim, his entire family had to walk 1000 miles to Pakistan taking with them only what they could carry. I still can’t imagine what that was like - he always told me that he still remembered two lines of people walking in opposite directions separated by a few metres during partition. He loved England and we all considered him to be more English than real Brits were!

Dad immigrated to the UK in his early twenties with a strong American accent which he had developed from watching American films and worked really hard to blend-in when he arrived in London. Instead of joining a Pakistani diaspora, he preferred to adopt local customs and over time, his accent became so polished, that you would never have known that he wasn’t English. He was just a thoroughly nice guy and endeavoured to always be a perfect Gentlemen. Everyone who met him, loved him.

My parents had a pronounced laissez faire approach to parenting but the deep cultural differences between their Pakistani and Germanic backgrounds made for some interesting conflicts that would mould both me and my sister.

I think that Dad was embarrassed to be a Pakistani – remember that he arrived in the mid-1960s and there was a lot of racism in England. Consequently, he was always trying to be British and not stand out. When he and Mum first met, Dad was initially embarrassed to say that he couldn’t eat pork for religious reasons and instead, told Mum that he didn’t ‘like’ pork. Mum couldn’t understand how this was even possible, since as a German, she had been brought up eating vast quantities of pork (and Germans cook pork extremely well). The story goes that she prepared him a delicious meal which they both really enjoyed and then after they had finished eating, she asked him what he had thought of the food and of course, he complemented her on her cooking. Dad recalls that her face broke into a big smile when she said, “…and you thought that you didn’t like pork!”

It was obvious from the start that I would never fit in since everything that I saw of the world would be seen through the spectacles of both German and Pakistani values in 1970s Britain.

This was brought into sharp context some years later when I was 17 and an Uncle and Aunt came to stay for an extended period. My Aunt suffered a number of miscarriages in Karachi and had come to the UK with its better healthcare in order to complete her pregnancy. They stayed for several months and every day when Mum and Dad were at work, Auntie would cook wonderful curries and although her food was truly fantastic, I did eventually become fed-up of spicy food and learnt to cook for myself.

Every evening, Mum would serve the meal which Auntie had cooked and everyone would sit down to eat. After we had all finished, Mum would ask whether anyone would like any more and then, sensibly clear up when there were no takers for seconds.

Something very subtle was going on here but I would only find out several years later, that my Uncle was actually hungry after every meal but couldn’t bring himself to ask for seconds and it turns out that he was visiting a curry house every lunchtime to buy boiled rice to eat before dinner. His reasoning? He was too embarrassed to ask Mum for seconds and desperately didn’t want to make a fuss!

Judgement comes from experience, and experience comes from bad judgement. Simon Bolivar

Learn from the mistakes of others. You can’t live long enough to make them all yourself. Eleanor Roosevelt

This is the exchange that he was expecting...

Pakistani version of asking for seconds at dinner (so as not to cause any offense)

“Would you like some more?”

“No thanks”

“Really? Please have some more.”

“No really, I am full”

“I must insist – please have some more.”

“OK, if you insist”.

German version of asking for seconds at dinner

“Would you like some more?”

“Yes please.”

So, you can see why the world must have been a confusing place for me!

While Dad had a very hands-off approach when I was growing up, education was extremely important to him. His Grandparents were apparently so wealthy that they had lived like kings and his Grandmother never wore the same outfit twice, donating all of her clothes to charity after wearing them. They then lost all of their money quite suddenly and from being really rich, they found that they now didn’t have enough money to live.

My Great Grandad insisted that they would rather skip meals to buy books if this ensured that their sons could have the best education. From that troubled start, all five sons rose to the top of their professions and valuing education became strongly embedded in my Pakistani roots.

Mum was born into a working-class German family and her Dad had been a tailor and veteran of the Second World War. He may have been a skilled tailor but sadly, he was not a successful businessman so there was never very much money at home. Her Mum however, was a thrifty German housewife who managed to bring up four daughters alone during the war, which would have been extremely challenging and was testament to her resourcefulness. Likewise with Mum, existence and survival would define her values too.

Mum left school at 14 to go to secretarial college whereas Dad had been university educated. Valuing our education was very much my Dad’s influence, but Mum was happy to support him.

Schools in North West London in the 1970s were poor and though my parents struggled financially, they managed to put my sister and I through prep school. They could not afford private secondary education, so Mum was determined to find the best state-run schools, since they felt that this would give us the greatest opportunity to go to university.

Mum is creative and enterprising and managed to persuade the local council to send me to a school outside our borough which had only recently changed from being a grammar school to a comprehensive. Whereas all grammar schools had very high standards and good teaching, they had no idea that by the time of its second comprehensive intake, the Westminster City School in Victoria, had gone rapidly downhill. It was also an hour’s commute for me requiring a bus and two tube trains each way and made it doubly difficult for me to make friends. My parent’s intentions may have been excellent but it wasn’t a good decision.

The long commute put me off volunteering to take part in school plays and sports teams and as a result, I didn’t have much of a social life and just a few close friends at school.

There was a lot of racism in 1970s Britain and being beaten up for being from an Asian background was fairly normal then. It even had a special word and a song – “Ding, dong the lights are flashing, we’re going Paki bashing”. It still makes me shudder today. I remember that leaving school and avoiding the skinheads was a challenge in itself, since beating up kids like me was fair sport to them.

Adolescence is a lonely time for boys and so it was for me. I wasn’t one of the popular kids and didn’t fit in wherever I went. After a while I realised that if I couldn’t be like the others, then I should celebrate this and made a point of trying to be different. However, as I was to learn, this didn’t really help me to make friends or lead to an easier life.

During this time, Dad was working from home in his workshop and I seemed to be very incidental to him. He would spend most of his time there and only come in for short bursts. Whenever he would see me, his face would break into a smile and he would say to me, “Yes please!” This meant that I now had to make him a cup of coffee – milk and two sugars and he drank a LOT of coffee. We were early adopters of the Braun coffee machines and used them so much that they only lasted six months before needing replacing.

His attitude to me completely changed when it was time for either the termly school report or parents’ evening, at which point he would become super-attentive and this would be followed by the inevitable family conference to work out why I hadn’t performed well enough. For Dad, whilst A-grades were expected, these were sadly quite rare on my report cards and I grew up feeling that I always HAD to work harder and perform better if I wanted to win his approval. This seemed really unfair to me since he’d never been a great student himself. Nonetheless, sons of Pakistani fathers had to be respectful and I would never be so insolent as to make this point to him directly.

Dad once told me that, when he was a young father, he had asked a mother what she thought the secret of good parenthood was, and she had replied that it was important to let her children develop by allowing them to question her. It is a credit to him that he did allow me to question him and this gave me great self-confidence and independence, though it would also cause us significant problems later on.

I made an important decision when I was 13 that I would fully commit to being the A-grade student that Dad wanted me to be, in order to win his approval. I confess that I am not a natural student but have a great work ethic and studied as hard as I could and did really well that year. After the exam results were out, I was so proud with how well I had done. I ran home and told him that I had managed to achieve the second-highest score in the school in chemistry. I remember that he smiled wanly and replied, “Next time, be first!” That was it. No congratulations or a hug – just do better next time. These words still smart today.

Not going to a local school meant that I didn’t have many local friends, so I decided to change this by joining the Air Cadets. Dad hated the army and initially didn’t want to let me go, so I had to firmly argue my case in a family conference before he granted me his permission to join.

I really enjoyed Air Cadets and even learned to fly an aeroplane, though frustratingly for me, my attitude of trying to make myself act like an outsider had prevailed and found that I was never to be popular in this group either. The Commanding Officer also didn’t like me, so while I passed all of the exams, I was never promoted beyond cadet.

Chapter 3. Goatanomics

The optimist proclaims we live in the best of all possible worlds; the pessimist fears this is true.

Or the story of the man, his Mullah and a goat.

I read what I assume is an apocryphal story some years ago and I feel that the underlying message is so important, that I wanted to dedicate an entire chapter to it. A man visits his Mullah and laments that he is unhappy.

“My wife is unhappy, my children are crying and

I don’t have enough money. What do I do?”

“Buy a goat!”

“What!”

“Buy a goat.”

“…but…”

“Buy a goat.” (forcefully)

…and the man leaves the Mullah looking dejected.

He returns the next morning looking even more unhappy.

“My wife is unhappy, my children are crying, I don’t have enough money and that BLOODY goat is shitting everywhere! What do I do?”

“Sell the goat!”

“What!”

“Sell the goat.”

“…but you told me to buy a goat.”

“Sell the goat.” (forcefully)

…and the man once again leaves the Mullah, though this time looking even more dejected.

However, he returns the following morning but now looks a completely changed man and this time, he is actually smiling.

“I am SO HAPPY now that goat is gone!”

As I said earlier, I don’t really think that the man, his Mullah or the goat really existed but I often think that this story can teach us a really important key to happiness. My thought process goes like this.

We all live in our own bubbles and sometimes find ourselves entirely consumed by problems which we know are not really that important (pressing deadline; impossible target, too much to do; can’t afford a skiing holiday…) but these problems still manage to consume much of our thinking time and this influences how we feel and live. We stop enjoying our food, our families and may even start avoiding our friends. We may appear pensive, distant and stressed and although there may be so much that is good in our lives, at this specific moment, we can’t appreciate it.

All of those missed opportunities to have great experiences - what a tragedy!

Then, when something really serious happens (terminal diagnosis; immanent financial ruin, a shark suddenly appears who is about to eat you, etc.) all of your previous problems instantly evaporate in a puff of smoke, as you now totally concentrate all of your attention to solving this serious, new problem.

I love to deliberate on the joy which we would suddenly experience were this new problem suddenly to disappear (you were given the wrong diagnosis; the bill was in Zimbabwean dollars; the shark was a vegetarian, etc.)

The problem is that we often can’t appreciate the perspective and importance of these problems in the wider context of our everyday lives. When my wife presents me with a problem that she deems both serious and insoluble, she is never comforted when I tell her that at least she hasn’t just stood on a landmine (since that would be much worse, or something equally banal).

“That’s NOT very helpful,” she always replies to me.

However, I think this approach can really be helpful to develop a sense of perspective for our problems and it reminds me to regularly reappraise how great life is here on planet Earth.

I don’t think that we are particularly good at considering what is genuinely important to us.

I love the scene in Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, when an extraordinarily arrogant character called Zaphod Beeblebrox is made to go into a terrifying machine called the Total Perspective Vortex, in order for him to see just how insignificant he is in the grand scheme of the universe. This machine is supposed to totally blow your mind when you see the vastness of the universe and just how puny and inconsequential we are in relation to it.

The joke is that in the story, Zaphod becomes the first person to leave the Total Perspective Vortex chamber without going mad, since he now really believes that he is worthy of his important position in the galaxy. Being Galactic President in the story may have helped him to believe this!

When you consider that we live on one of eight planets in our solar system which orbit the sun in a galaxy called the Milky Way which itself comprises of an estimated 100 billion stars, and that this is just one of an estimated 100 billion galaxies, you realise how totally insignificant our planet and life on it becomes…

When I started studying for my MBA some years later, Barclays Bank was kind enough to offer me a £10,000 interest-free loan for my tuition fees (£10K doesn’t go very far these days but in 1993, this was a fair sum of money).

Dad had volunteered for the company to pay for my MBA but I felt that an interest-free £10K was an offer too good to pass on, so I applied and soon had an additional £10,000 in my bank account and decided to buy a Supercar.

Although I couldn’t really afford it, this new windfall enabled me to buy a two-year old Toyota Supra Turbo, which could travel 150mph, had leather upholstery, climate control, electric seats, air con and lights which flipped up and down (this was the early 1990s, remember). Most importantly, it was powered by a 3-litre turbocharged engine and if I double-declutched, put the car into second gear and floored it, then even at 70mph, I could squeal the tyres. For a 23-year old, this was heaven!

However, where does this fit in with Goatanomics, I hear you ask?

Well, when the car was delivered, I was initially deliriously happy. But then I discovered a small problem with the transmission and I noticed that when I changed from first to second gear at less than 1600 revs, I could detect a faint noise coming from the engine that shouldn’t have been there. It may have been a barely-audible whooshing/rattling noise but the important thing was that I could hear it and when I drove the car, this is what I listened out for. It drove me nuts!

Whilst my friends were really awed by how amazing this car was, all I could hear was this awful noise and I would make a point of drawing their attention to it every time!

Eventually I took it back to the dealer and they stripped and rebuilt the entire transmission, after which the noise disappeared - but for two weeks, I didn’t enjoy my amazing new car. What a shame! - isn’t this just like life?

You might be interested to know that we did take this car to the Alps (I called her Georgina) and drove extremely fast on the Autobahns, one time managing to hit 146mph (rain stopped me pushing on to 150mph. It’s worth pointing out that there were no speed limits in place). When we returned from the trip, just two months after buying the car, I sold it, with my supercar craving having been satiated.

It is as true today as it was then, but a young man can’t afford both a house and an extravagant car at the same time. Sometimes hard choices need to be made – I bought a house, so the car had to go.

I conclude from this lesson that if you can, take time out of every day to smell the flowers; look at the beautiful buildings and trees; take a walk; enjoy your coffee; spend quality time with your friends and family; slow down and consider whether your problems are really so serious that you can’t enjoy the now.

In the words of Jack Nicholson’s character Melvin in the film As Good As It Gets, the best things about life are described as ‘good times and noodle salad’. If you haven’t watched this film before, then it is a life changer and Melvin really did master the lessons of Goatanomics, although he didn’t realise this at the time!

There is a paperback version, e-book version and audiobook version all available on Amazon UK and all other worldwide Amazon sites.